Sierra Leone’s Newest Fight

Posted on Dec 1, 2017

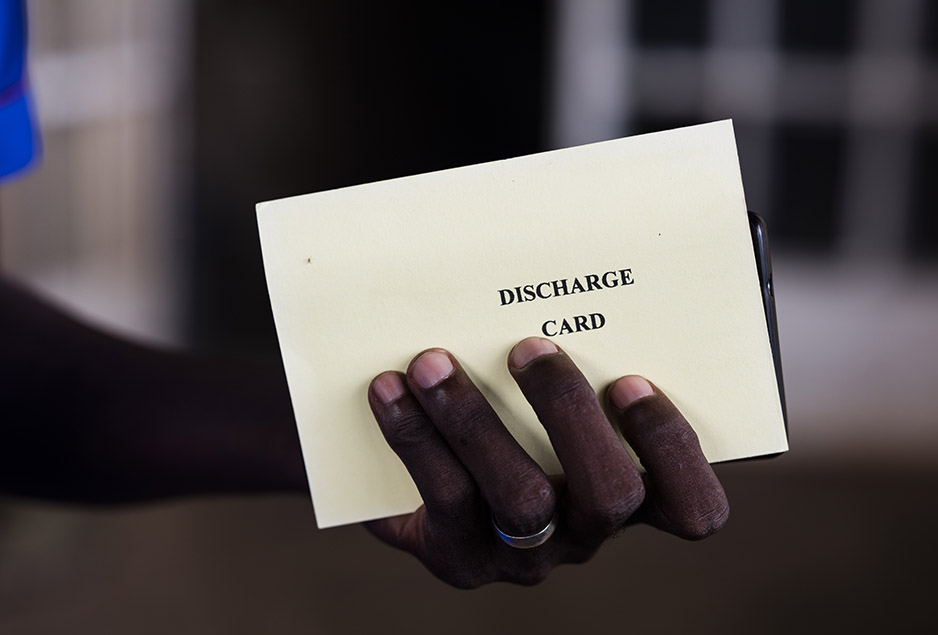

It was a landmark, a triumph, a watershed moment—without fanfare. On Oct. 6, two doctors stood under the awning of a yellow hospital on the western edge of Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, and gave instructions to the first patients to be discharged from the first tuberculosis treatment program of its kind in the country.

“If you have a problem, if you have a question, call us,” one doctor said. “You have my number.”

“What can we eat?” asked one of the patients.

“Everything,” the doctor said.

“Should I wait to go back to work?” asked another patient.

“You can continue to work as long as you have energy,” the doctor said.

Quiet settled over the group as the five men proved too chaste to ask another logical question.

“You can live your normal life,” a second doctor volunteered. “You can be with your wives.”

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis—an advanced, cruel, and hard-to-treat version of standard TB, known as MDR-TB—has been spreading inside the West African country for years. The World Health Organization estimates that 700 people in Sierra Leone suffer from the disease, but admits that far higher numbers are “a frightening possibility for the nation.” A year ago, none of those people had received meaningful medical care. A handful of the lucky ones had been isolated in hospitals, so they could waste away without their bacteria-laden coughs infecting others.

But that's now no longer the case thanks to the passionate work of Program Manager Dr. Linda Foray, of Sierra Leone’s National Leprosy and Tuberculosis Control Programme, and the steadfast support of Partners In Health, with funds from USAID's TB CARE II. In April, they launched the nation's first MDR-TB treatment program, at Lakka Hospital. It currently treats 84 MDR-TB patients and counting. And at 2 p.m. on that Friday in October, the first people in Sierra Leone to survive the disease waved goodbye to staff and fellow patients and walked out the gravel drive.

The subdued mood felt oddly appropriate.

No one should have to fight MDR-TB; its existence is a testament to our decades of collective indifference. A cure for TB was invented in the '40s. Rich countries quickly all-but eliminated the disease. Poor countries, however, lacked the money and health care systems to tackle TB.

So TB continued to spread, through mining camps, farms, homes, cities, and more, everywhere from Latin America to Asia. In the '90s, the rise of HIV, which weakens immune systems, caused TB infection rates to skyrocket. (From 1995 to 2005, the prevalence of TB increased by factors of five in many poor countries.) Simultaneously, poverty, wars, and preventable epidemics, including Ebola, caused TB programs in poor countries to fall apart.

TB patients who had managed to get medication found themselves having to stop midway through treatment. And the TB mycobacterium, wounded but not killed, grew resistant to the most affordable and effective drugs. It became MDR-TB.

It’s hard to assess exactly how much Sierra Leone is paying for our decades of disregard. The country holds the sad distinction of having one of the highest TB rates, which suggests that MDR-TB rates also should be exceedingly high. But the MDR-TB data is spotty.

“In the scientific world, some say, ‘Oh, the prevalence of MDR-TB in Sierra Leone is very low,’” says Dr. Marta Lado, PIH chief medical officer in Sierra Leone. “But if you didn’t have any way of detecting it, reporting it, or treating it, of course your ‘data’ about the prevalence is going to be low.”

And “low” is of course its own form of condescension. In the United States, which has roughly one-tenth as many MDR-TB sufferers as Sierra Leone, a single new case causes alarm.

Sierra Leone clearly needed an MDR-TB program. Two years ago, PIH leaders started pushing for one, and in August 2016, they began advising and supporting Foray. Leaning heavily on experience with MDR-TB in Peru, Haiti, Lesotho, and elsewhere, PIH leadership helped lay out how and where to treat people.

Most notably, the team traded crude chest X-rays and colored dyes for new GeneXperts, toaster-sized devices that quickly and simply analyze a person’s sputum for telltale DNA.

The GeneXperts added a sense of urgency. While training with them in March, a PIH lab technician diagnosed a patient with MDR-TB but the program, still evolving, didn’t have the medication to treat her within the country. PIH leadership pushed everyone to step up efforts immediately—not just out of solidarity, but also as a matter of doctrine.

“PIH has one main idea: We need to support the improvement of the health care system in this country,” says Lado. “If people go to the hospital and get charged a lot of money, or don’t get high-quality health care, or don’t get an accurate prescription, or there´s a problem of power and water supply, or the admission process is inefficient, or there’s no waste management and everything’s dirty, then people aren’t going to come to the hospital. We said, ‘We can put all the GeneXpert machines that we want in the country, but if we don’t have the medication to treat patients, we’re not going to help people get better, and they’re not going to come to the hospital.’”

Staff found the right drugs and enrolled the patient in treatment, and the program officially began in April. They predicted 50 patients in the first year. Just eight months along, they're already helping 84, in part because of 20 new GeneXpert machines in the country.

“They’re seeing one new patient every day,” says PIH Deputy Policy and Partnership Director Dr. Bailor Barrie.

At 4:30 p.m. on that historic Friday in October, MDR-TB survivor Joseph Alan Mansaray reached his aunt’s home in Freetown. The 47-year-old father, husband, and plumber had left a year and a half earlier when he, like others, had voluntarily isolated himself in Lakka Hospital. His aunt, waiting at the side of the road, greeted him and the PIH staff member who had accompanied him. She had not expected to ever again see Mansaray outside the hospital.

“Thank you,” she said.

Mansaray agreed that the discharge ceremony wasn’t exactly festive, but for him, the reason was clear.

“So many friends died while we waited for treatment,” he said.

* The program described in the report above has been funded through the TB CARE II project and is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. *