Training for Ebola: An Interview with PIH's Dr. Sara Stulac

Posted on Oct 8, 2014

As the Ebola outbreak continues to unfold in West Africa, frontline health care workers are facing enormous challenges. More than 400 health care workers had been infected with the virus as of Oct. 5, and more than 230 had died from it, according to the World Health Organization. As PIH and its partners respond to the outbreak, we are acutely aware of the personal risk our clinicians are taking and are seeking to implement robust trainings and systems to minimize the risk and ensure that we deliver the highest-quality care possible to patients.

Last month Sara Stulac, Partners In Health’s deputy chief medical officer, and several colleagues, including Joia Mukherjee, Anany Gretchko, Pierre Paul, Sheila Davis, and Corrado Canceda, attended a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention training in Anniston, Alabama, designed for clinicians who will be responding to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. We asked Dr. Stulac to share her impressions of the training and discuss PIH’s evolving response to this historic health crisis.

Can you tell us a bit about the CDC training?

It was a three-day training, focused on preparing clinical providers to deliver care in the safest possible manner. The group was mostly clinicians, and was taught by CDC staff as well as clinicians who had recently returned from West Africa: a nurse from Médecins Sans Frontières and a doctor who works in infection control at Boston University who had on-the-ground experience with the current outbreak.

What did the average day look like?

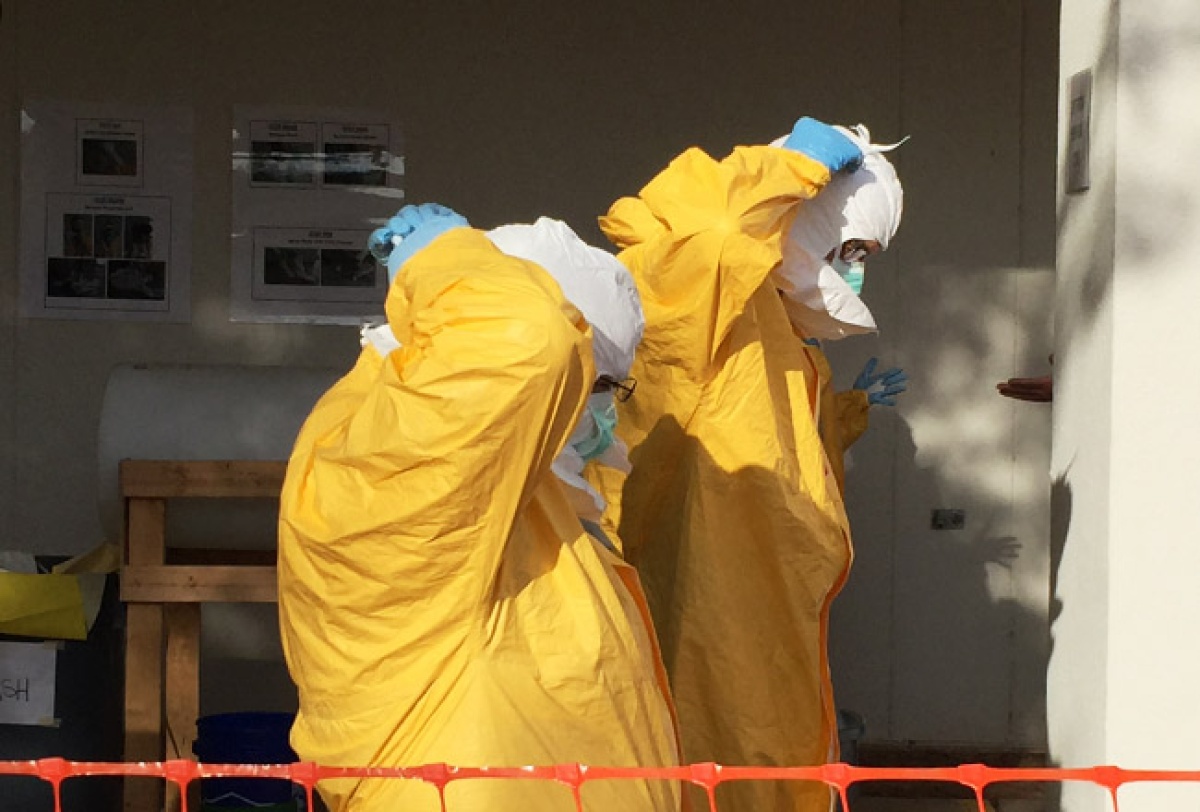

We spent a few hours each morning in a classroom, discussing everything from logistics to new treatments in the pipeline to how communities are carrying out contact tracing. The afternoons were spent working in mock Ebola Treatment Units. We spent several hours going through the process of donning and doffing the personal protective equipment (PPE) and doing exercises with mannequins. We would run through mock scenarios: For instance, there’s a patient lying under a tree in the courtyard who just came in and collapsed and is vomiting and is now unconscious. What do you do? And how do you do it safely?

What aspects of the training surprised you?

This is such an infectious virus that we need to be extremely vigilant, following every protocol.

Doffing, or taking off, the PPE was a sobering experience. This is one of the highest-risk activities, because that’s when your protective equipment almost certainly has fluids on it from patients who are infected. If you don’t take off each protective item in a very specific order, following a very specific procedure, you are putting yourself and others at risk. And keep in mind that this happens after a clinician just finished working a shift in an intense environment. They are tired and they’re hot and they need to get out of this equipment, yet it has to be done methodically and carefully. In many ways you need to commit the process to muscle memory.

While this was certainly sobering, we weren’t at any risk. We weren’t doing real work; we were doing pretend work with mannequins. So we had this tiny, tiny taste of the challenges and risks practitioners will encounter in the field, and that gave us a huge appreciation for how serious this type of preparation and training is. This is such an infectious virus that we need to be extremely vigilant, following every protocol.

Are there challenges in terms of getting and securing enough PPE?

Yes, there are supply chain issues and procurement issues that need to be addressed. I’d like to emphasize, though, that PPE is not the full answer. PPE is one very important tool that is needed to provide safe and effective care for patients. But we still need to have medicine, we still need to have transport, we still need to have the “staff, stuff, and systems.” But PPE is just one specific thing that is in obvious shortage right now.

Also, keep in mind that the supply chain for very basic medical supplies in the countries and areas where we are working were never perfect to begin with, and this outbreak has put an enormous strain on every aspect of very fragile health systems, including the supply chain. But we are starting to see the large, global mobilization of resources with significant financial commitments from the U.S. government and others. This is very important, and we need more such commitments.

There is a severe stigma around Ebola. Are there lessons PIH can draw on to reduce stigma and provide dignified care?

And with the right supportive care, the cure rate can be so, so, so much higher than it is now.

PIH has learned a lot of lessons in a lot of other places that we can apply to addressing the kind of stigma and the need for dignified and high-quality care with Ebola. We need to remain humble, knowing that we haven’t worked in Liberia or Sierra Leone, so it’s a new disease for us, and it’s a new situation and cultural context, which is so important to understand. This is why we’re grateful to be working with organizations that have been working in these countries at the community level for many years.

As a clinician, however, I understand the tension between needing to protect yourself and wanting to have that personal connection with patients. When you’re dressed in a space suit, how can you possibly feel close to a patient or let them know that you care for them and that you’re trying to provide them good care? You may not be able to touch patients directly or talk to patients without a piece of plastic and PPE between you, but you can provide for their needs. You can provide food—providing food goes a really long way. There’s not an antibiotic or treatment for Ebola; it’s all supportive care. And with the right supportive care, the cure rate can be so, so, so much higher than it is now.

And we are working on ways to work closely with the communities PIH and our partners are serving. Getting community members involved, getting people who have recovered from Ebola to speak with neighbors, is one if the best strategies I can think of. This same strategy has helped us reduce stigma around HIV in other countries.